40 Years of the Yamaha DX7 – Ring Those FM Bells!

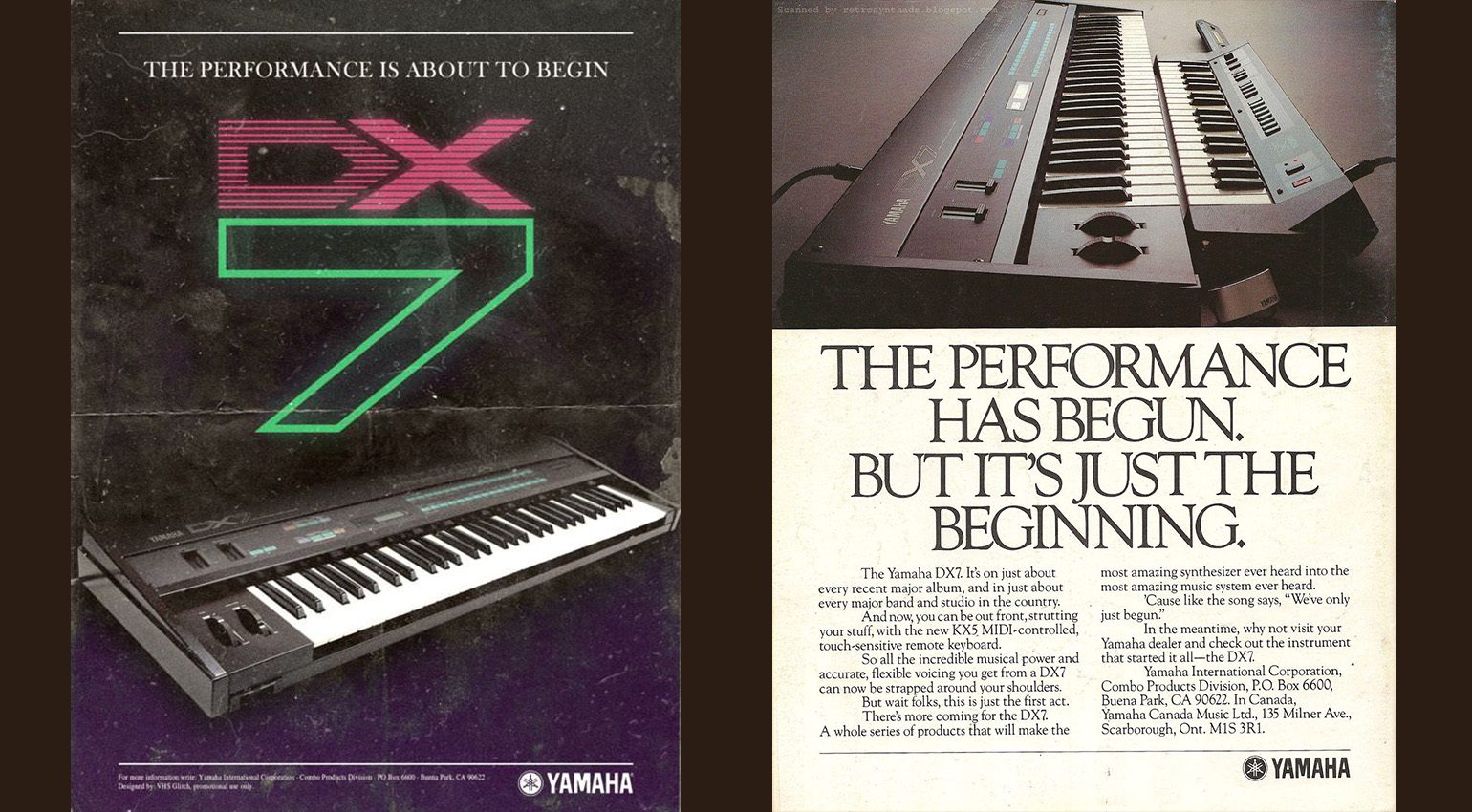

The Yamaha DX7 went on sale for the first time on May 29th, 1983. To mark this significant anniversary, we take a look at this technological and cultural marvel that dominated the world of synthesizers.

When I’m bored or having a casual chat with like-minded synthy friends, I like to debate which synthesizers were game-changers. I have to be careful using that term as our Editor hates it. However, in the context of an historical piece, I figure I’m good!

These discussions can often lead to some interesting results. The synth which is always agreed upon is the Yamaha DX7. It undeniably changed the world of synthesizers for ever and in a multitude of ways, whether you think that was good or bad.

The Yamaha DX7 ushered in the era of digital synthesizers. It gave birth to a new industry of 3rd party presets and set a bar for price and build quality levels. The sounds it gave us were new, fresh and unheard of outside a science lab.

The Unmistakeable Sound of the DX7

Of course, it also gave us enormous ubiquity. So impressive was its sound, playability and level of cool that it featured on almost every hit pop record. It also became the darling of the ambient scene. It defined the sound of the mid to late 80s, a sound resplendent in glassy chimes and crisp brass. And who can forget the amazing basses and electric piano tones.

There’s not a person alive who went to high school discos in 1985 for whom the DX7 E PIANO patch doesn’t cause a stirring in the loins. The opening refrain on songs like Whitney’s “Saving All My Love For You” saw teenage boys summon the courage to ask the girl across the hall for a dance. Every R&B ballad used it because it was full of soul and expression.

E BASS 1 heralded the rush of the opening scene of Top Gun as Kenny Loggins soundtracked F-14s departing the deck of an aircraft carrier. It gave us that funky bass line in A-ha’s “Take On Me” or tastefully backed Howard Jones’ soulful “What Is Love”. Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got To Do With It?” was almost all Yamaha DX7, save for the LinnDrum and electric guitar.

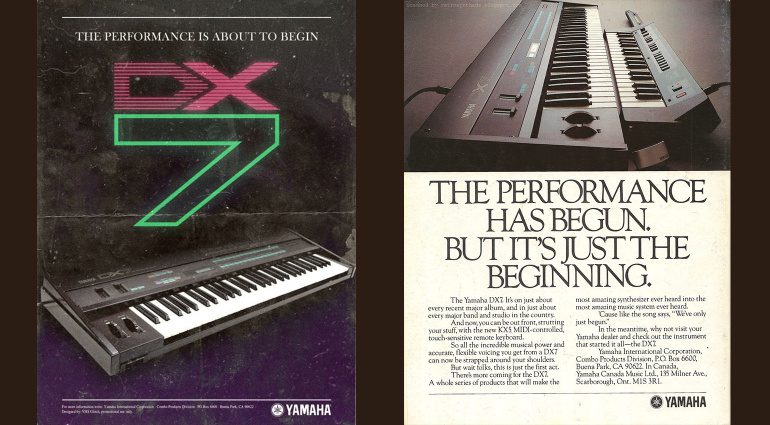

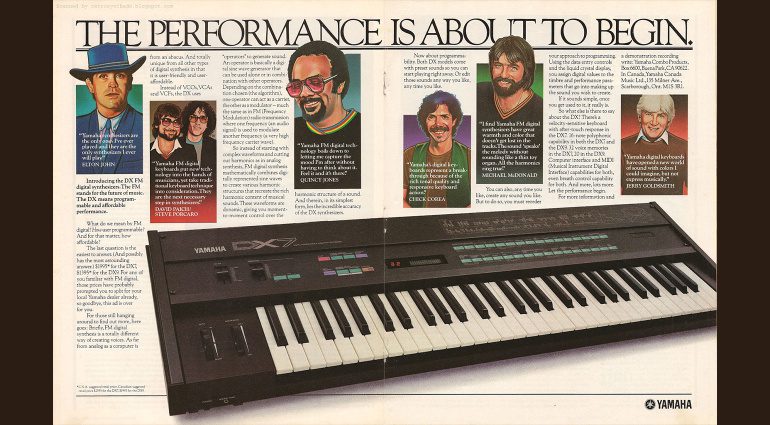

The Yamaha DX7 was everywhere but not because it was forced down our throats as part of some full-on marketing scheme. In fact, Yamaha didn’t do any major advertising during the first year of it being on sale. The sound of the DX7 sold itself.

For those of us who were around at the time, the DX7 was hard to get. Units had been sold and paid for in full before the containers hit the dock from Hamamatsu. So how did Yamaha literally destroy the competition 40 years ago this month? Let me tell you…

The Technology

Dr John Chowning is widely known as the man who discovered FM synthesis. During his computer music studies at Stanford University, within the CCRMA facility, Chowning stumbled across the technique when he began modulating one sine wave (the carrier, connected to the audio path) with another sine wave (the modulator, only connected to the carrier).

He found that by increasing the frequency of the modulator, the carrier wave shape became complex and sounded very different. Experimenting with the frequencies of both the carrier and modulator, he could conjure up even more complex waveforms with lots of harmonics and inharmonics.

Yamaha later found that you could create even more sonic complexity by feeding the output of an operator back in on itself. These methods delivered tones that no other synthesizer had managed before. Excited by this discovery, he continued his research and eventually had enough data to get the method patented by Stanford. Patents were, and still are, one very good way of generating income for universities. The DX7’s patent would become Stanford’s most lucrative in its history.

Yamaha Take the Bait

Stanford began to try and interest companies in licensing this technology. Given that this synthesis method was incredibly good at replicating organ sounds, they tried companies like Lowery and Hammond, but neither of them took it on. Eventually, in 1973, Yamaha sent a team of engineers to the U.S. where they decided this would be something they could work with.

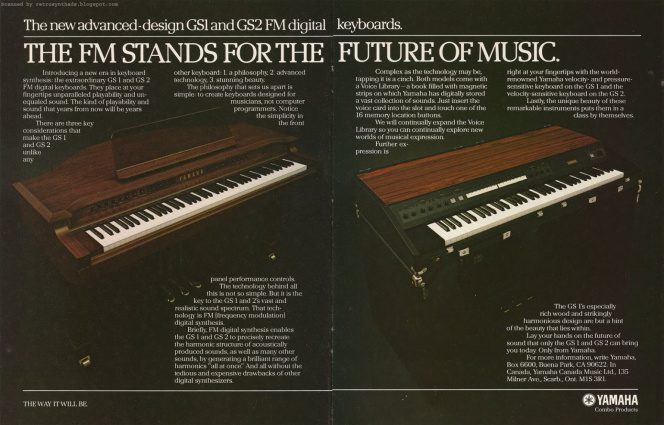

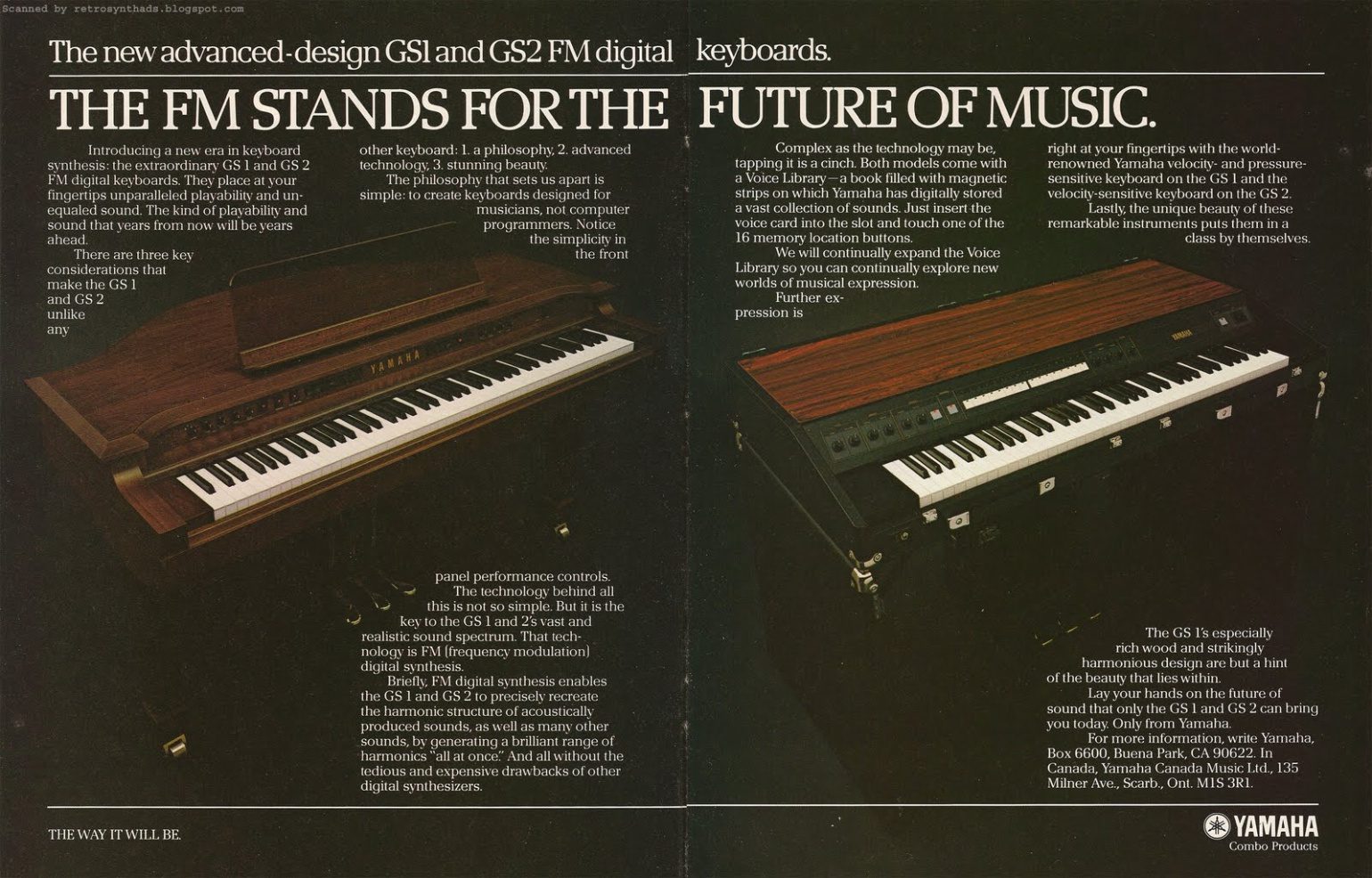

The deals were signed and they took the technology back to Japan. Many years were spent refining the method, working closely with Chowning along the way. Finally, some 7 years later in 1980, Yamaha released their first commercial FM instrument, the GS-1.

The GS-1 resembled a baby grand piano, with its large wooden case and legs. It was a preset machine, with no user programmability. Presets could be added via a magnetic strip reader. A year later, the GS-2 followed with a built in case and smaller keyboard.

Both these instruments used pairs of operators, each containing one carrier and one modulator. These would then be used to cross modulate other pairs within the instrument. By 1982, Yamaha had further reduced this technology to fit a slightly cut down version into the CE20 and CE25.

But it was in 1983 that Yamaha released the FM synth that would change everything. They abandoned the cross-modulation method used in the GS and CE synths. This required complex stand-alone programmers to create the patches and save to the synth’s memory.

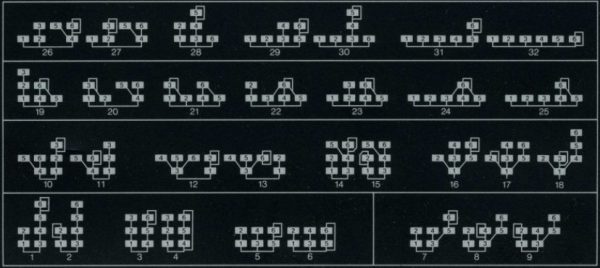

Yamaha’s engineers decided upon an algorithmic approach to further simplify the programming process. They assembled 32 algorithms, or combinations of operators, from 6 operators that could be used as the starting point for almost any sound the user cared to create.

Manufacturing

Another key to the Yamaha DX7’s success was Yamaha’s ability to reduce the FM technology from hundreds of microchips into just a handful of integrated circuits, or ICs. Yamaha had begun building factories to mass produce these chips at low cost which in turn allowed them to mass produce the DX7 at a low price. This strong ability to keep production completely in-house meant that Yamaha were on to a winner.

MIDI

It is safe to say that the timing of the DX7’s release was as crucial as it was fortuitous. The MIDI standard was in the last stages of ratification and Yamaha, whilst not being the first to add MIDI to a synthesizer, were the first to exploit its potential properly.

Their keenness to build MIDI into the DX7 meant that early models weren’t fully compliant and the Mk.I DX7 famously only went to 100 on MIDI velocity and not the agreed 127. However, it did not harm the success of the DX7 and it quickly became the master keyboard of choice because of the brilliant and eminently playable keyboard mechanism.

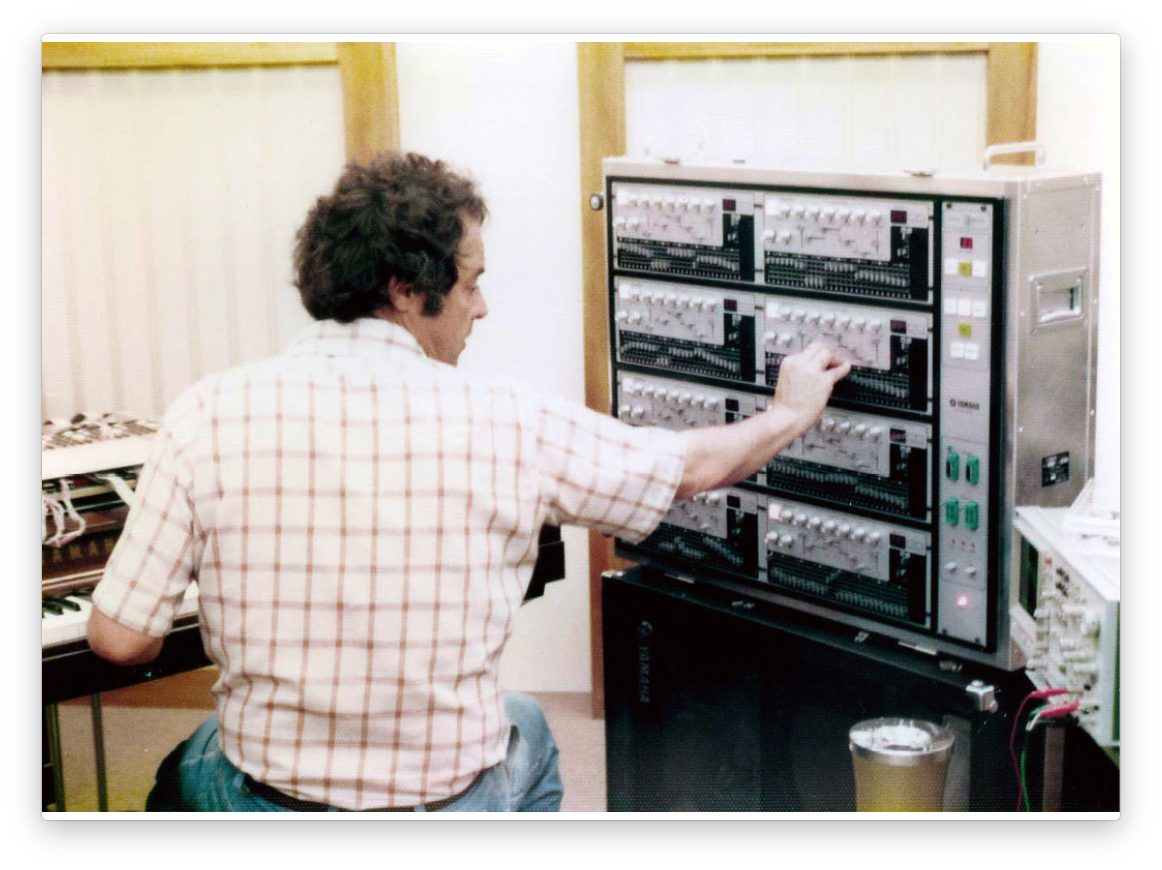

But within a year or two of the DX7’s launch, Yamaha had released the QX 1 sequencer, KX88 controller, RX11 drum machine, TX7 FM Expander and the mighty TX816, eight DX7 engines in a 4U rack unit. The TX816 delivered 8 part multi-timbrality and 128 note polyphony. In 1984, this was unheard of!

Each of these units featured MIDI, enabling the user to chain together everything they needed to make a full blown production. Yamaha called this Y-CAMS; the Yamaha Computer Assisted Music System.

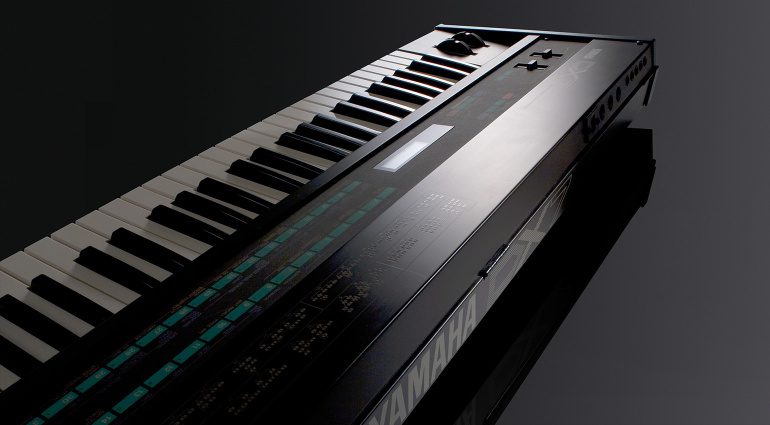

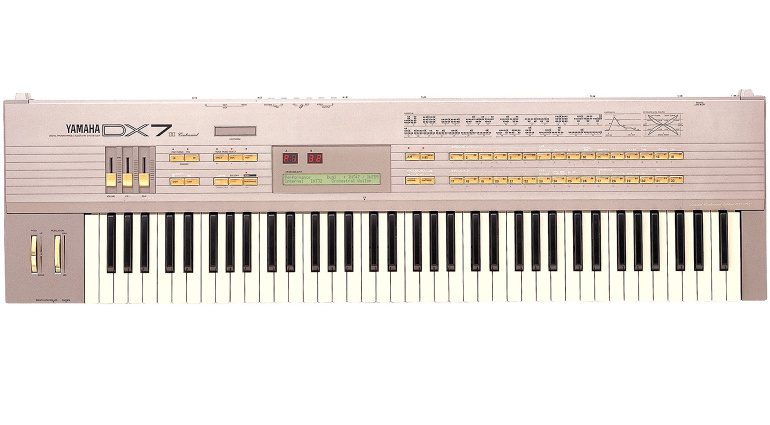

Design

The most noticeable thing about the Yamaha DX7 at the time was its distinct lack of knobs. This was a very deliberate choice on the part of the DX7 design team, as Yasuhiro Kira, a designer at Yamaha’s Design Laboratory points out…

“We removed all physical controllers except for the keyboard, using smooth membrane switches, something relatively new for a musical instrument. In utilizing this switch-based digital control for all aspects of its operation, the DX7 gave a clear message to that player that here was a synthesizer completely different to all those that had gone before.”

The DX7 eschewed wood in favour of a metal and plastic case, and was famously brown. This brown was a hangover from Yamaha’s ill-fated YIS (Yamaha Integrated System) concept. Kira-san explains…

“Adding these membrane switches to the design, it was vital that we make use of a color scheme that maximized their visibility. To achieve a clear contrast with the dark brown of the body, we used a vivid green for the panel that we came to refer to as “DX Green.” DX Green was eventually used on variety of products, and it came to symbolize digital technology.”

Getting The DX7 Sound Today

The sound of FM has never truly gone away and is currently enjoying somewhat of a renaissance. As with many synthesis methods, it goes around in circles. Each time, clever people come up with easier ways of doing what was once considered complex.

Yamaha themselves brought FM back to the fore with the Montage & MODX synths. Korg gave us the opsix and Volca FM (as well as the MOD-7 engine in their workstation ranges) and companies like Elektron used FM in their brilliant Digitone unit.

French new kids on the block, Kodamo, took FM beyond anyone else with their debut instrument, the EssenceFM. 300 notes of polyphony, freely configurable algorithms and a graphical UI that utilises a large touch screen.

On the software front, there is the free DEXED plugin as well as Arturia’s excellent DX7 V, available separately or as part of their V Collection. My personal favourite is Plogue’s Chipsynth OPS7 which sounds the closest to the original hardware of any plugin.

There are even clever people who have got 8 instances of DEXED running on a Raspberry Pi, effectively giving you the same sonic capability as a TX816!

Legacy

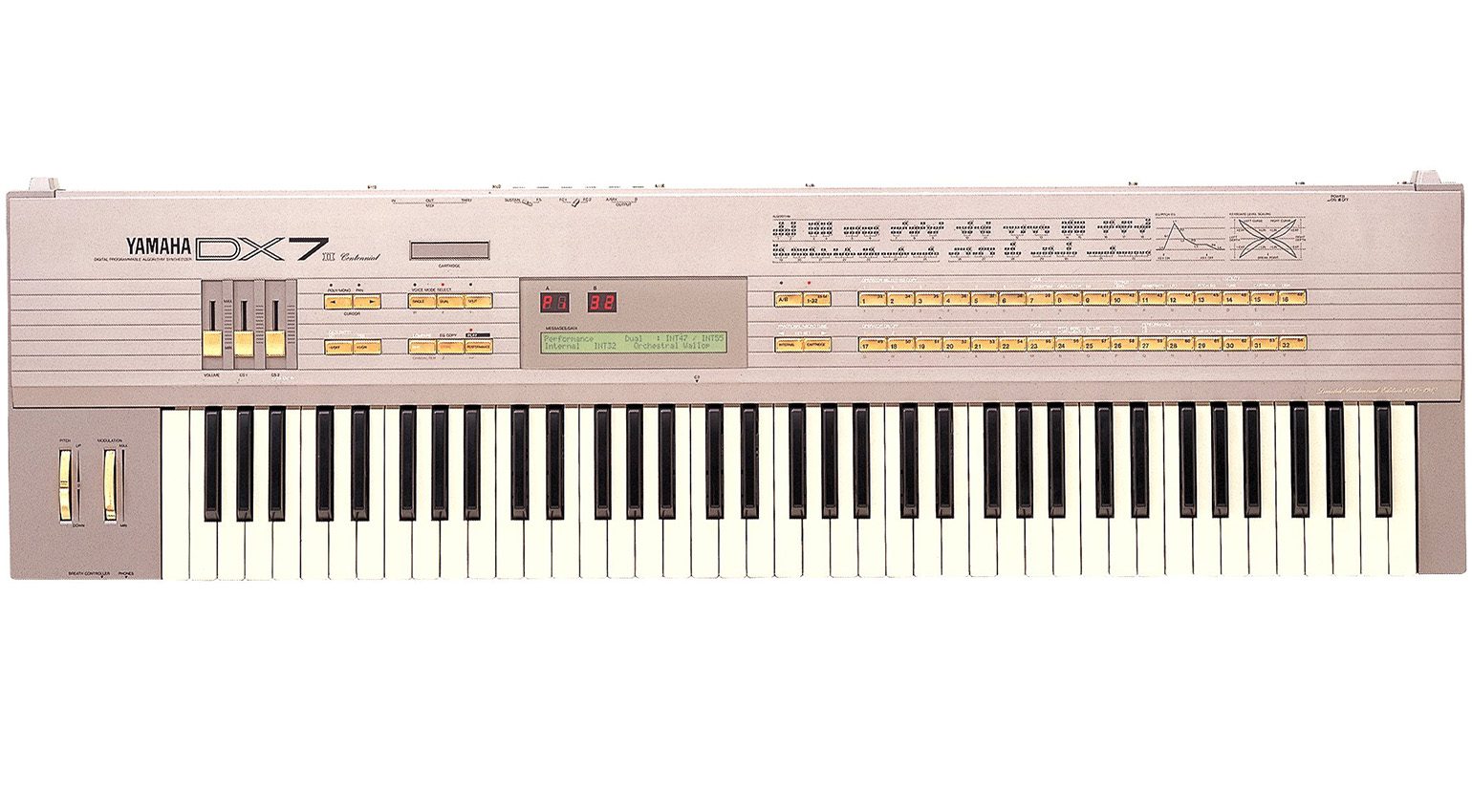

The Mk.I Yamaha DX7 was replaced by the MK.II in late 1986. There were four variants with the DX7S being the most basic. The DX7II-D and DX7II-FD delivered bi-timbrality and some deeper programming capabilities. The latter also had a built-in 3.5″ floppy disk drive.

A hugely limited Centennial edition was released in 1987 to commemorate Yamaha’s 100th birthday. This had 76 keys, a distinct champagne finish, glow in the dark keys and gold plated buttons!

But the writing was on the wall when, at the same time, Roland released the D-50. This took digital synthesis to a new level, incorporating PCM samples. It effectively killed off the DX7 and Yamaha had to play catch up with the SY series. The SY77 and SY99 married together samples (AWM) and an advanced version of FM (AFM) and began to claw back some of the market share.

At the end of the 1990s, the FS1R briefly reintroduced FM to the Yamaha line up. Now with 8 operators, 88 algorithms and formant shaping, it suffered from the same programming complexity as its forebears. The tiny screen meant programming this powerful synth was like painting the Sistene Chapel through a letterbox. It sounded magnificent and is highly sought after today.

It was only with the Montage and MODX that Yamaha really went to town on FM again in the 21st century. Pairing it with the latest AWM technology, it revived the concept first seen in the SY series. This time it would benefit from the 8 operator format seen in the FS1R and some amazing performance features, like the oddly named ‘Superknob’!

Many Happy Returns!

Whether you love it or hate it, the Yamaha DX7 broke new ground and changed the way hardware synths were perceived, made and used forever. It taught us a lesson that sometimes, too much of a good thing isn’t that great. It also showed us that giving a complex synth a small screen and a ton of menu-diving wasn’t conducive to great music making.

However, it also gave us more affordable technology. It almost single-handedly kick started the 3rd party preset industry and it spawned an era of MIDI enabled equipment that allowed us all to create multi-instrumental music with relative ease.

So, happy birthday, DX7! May your bells ring long and true!

* This post about the Yamaha DX7 contains affiliate links and/or widgets. When you buy a product via our affiliate partners, we receive a small commission that helps support what we do. Don’t worry, you pay the same price. Thanks for your support!

5 responses to “40 Years of the Yamaha DX7 – Ring Those FM Bells!”

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Facebook. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from Instagram. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information

4,7 / 5,0 |

4,7 / 5,0 |

My all time favourite synth! Not my best synth, not by a long way, but for some completely indescribable reason, it became the synth I wanted far more than anything else. I used to draw them in my books at school back in the 80’s! If I could be transported back to any place and any time in history, I think it would be the Yamaha factory in Hamamatsu, May 1983 🤣👍

I remember when I was in middle school in the mid 80’s, our school chorus was invited to perform at one of the theme parks in central Florida (it might have been Disney or Epcot, I can’t remember). I was the accompanist on piano for the chorus. When we got to the stage to perform, instead of an actual piano, what was provided was a DX7 ii, with no instructions. It just sounded cheesy and completely wrong for our singing, and 13 year old me kept trying to change the presets mid performance trying to find something that worked.

“There’s not a person alive who went to high school discos in 1985 for whom the DX7 E PIANO patch doesn’t cause a stirring in the loins. The opening refrain on songs like Whitney’s “Saving All My Love For You” saw teenage boys summon the courage to ask the girl across the hall for a dance. Every R&B ballad used it because it was full of soul and expression.”

Saving All My Love… was actually not a DX7 but a Rhodes piano outfitted with the Dyno-My-Piano modification.

It’s a matter of some debate, with a sizeable contingent suggesting it’s actually a TX816 played via a KX88 by Robbie Buchanan. Either way, the point I was trying to make was that so many R&B ballads featured that sound and, to this day, it invokes warm tingly feelings in the nether regions 😉

Glad you mentioned Plogue’s OPS7.

A true VST gem for DX7 revivalism.