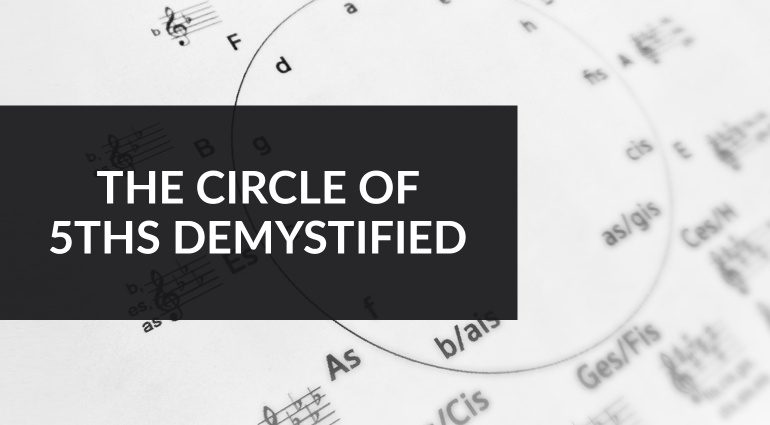

The Circle of Fifths Demystified

When the term “Circle of Fifths” comes up, many music students fall into an unreasonable panic. But there’s really no reason for that: Once you understand how the Circle of Fifths works, it becomes an indispensable tool for all your musical endeavors. For example, knowing the Circle of Fifths makes quick work of tasks like finding the right key and key signature for a song, identifying the notes of a scale, and transposing songs. Read our tutorial and the Circle of Fifths will become your new secret weapon!

When it comes to the Circle of Fifths, it’s the same as with everything else: you have to understand how something works before you can use it properly and benefit from it. For this reason, we’ll first look at the Circle of Fifths in detail and then I’ll explain exactly how it works.

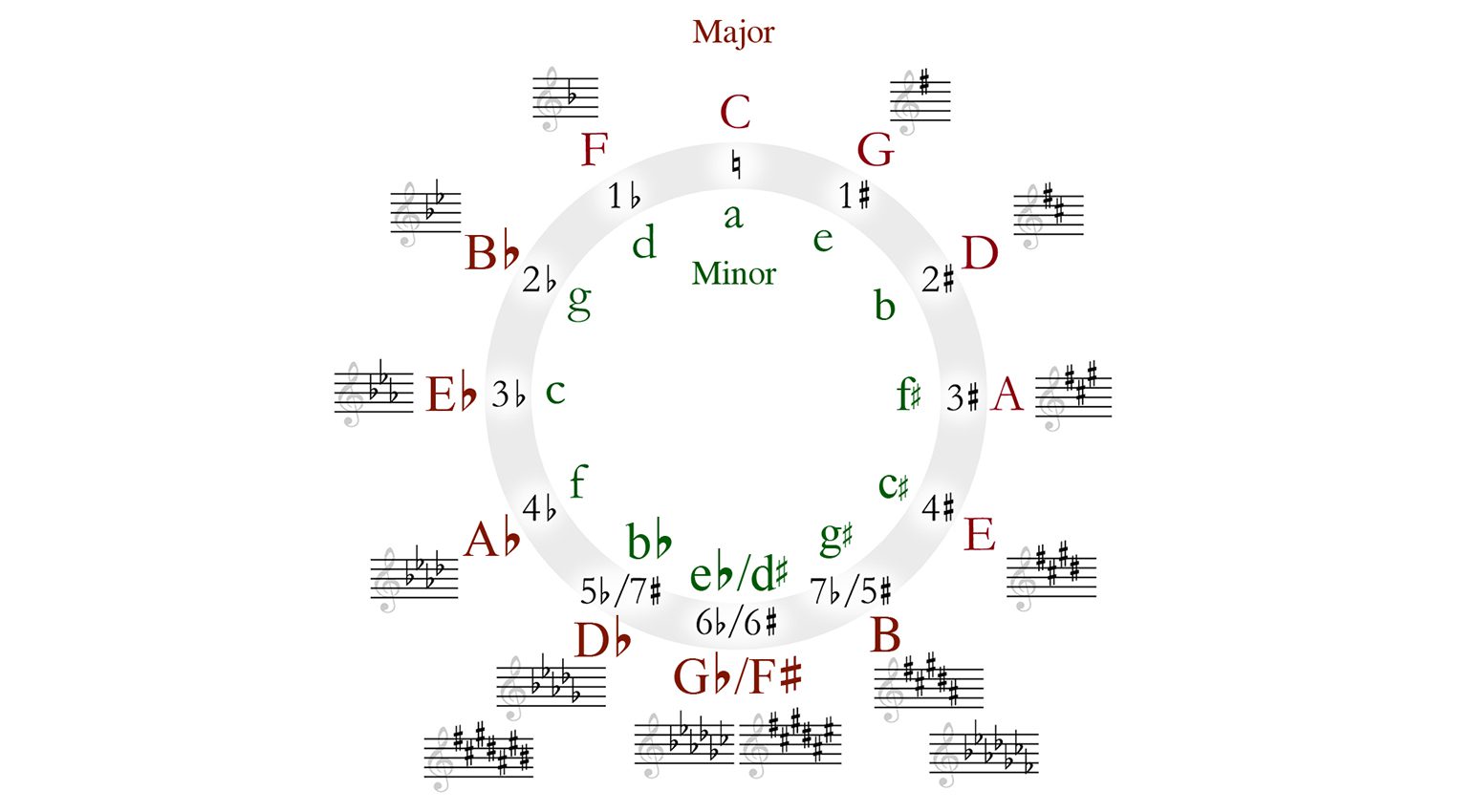

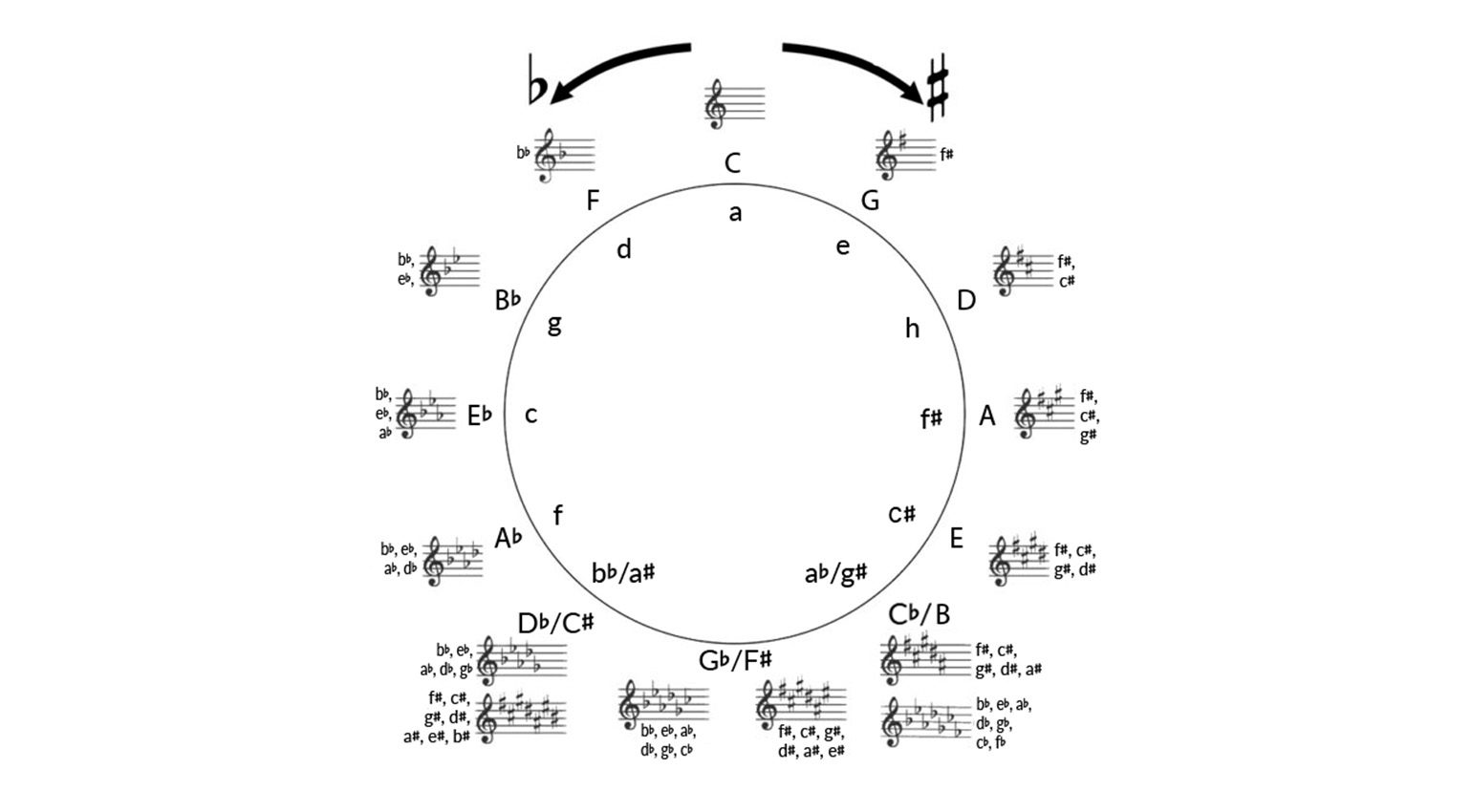

Circle of Fifths · Source: By Jpascher – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25711332

What is the Circle of Fifths?

In music theory, the Circle of Fifths is a series of twelve notes arranged in a circle at intervals of perfect fifths. If you move from the C at the top clockwise in intervals of fifths, you get the keys with a ♯ (sharp accidental) with an increasing number of accidentals. Moving counterclockwise from C, you get the flat (♭) keys. In its most common layout, it shows not only the major keys but also the associated parallel minor keys, which have the same accidentals. Looking at the Circle of Fifths, it becomes clear that pitches can also have two names, depending on whether they are part of a sharp or flat key. This is called enharmonic equivalent.

Why is it called the Circle of Fifths?

The outer circle of the Circle of Fifths shows the major scales. If you start at the C at the top and move in a clockwise direction, the interval to the next scale is a perfect fifth. In this direction, the accidental ♯ is used. If you move from the same C counterclockwise to the left, the distance to the next scale is also a fifth, and a flat accidental is used. The inner circle shows the parallel minor key associated with the major key at the same position, which uses the same number and type of accidentals as the major key. Their spacing is also always a fifth in both directions, left and right. The number of accidentals increases steadily on both sides – on each step away from C, one more sharp or flat appears.

Basically, the Circle of Fifths is an overview that shows you how many and which accidentals are in each key. But as we’ve already mentioned, it’s important to understand how this overview works. Once you’ve mastered it, you won’t need to look at it anymore to determine the keys or the notes of a scale.

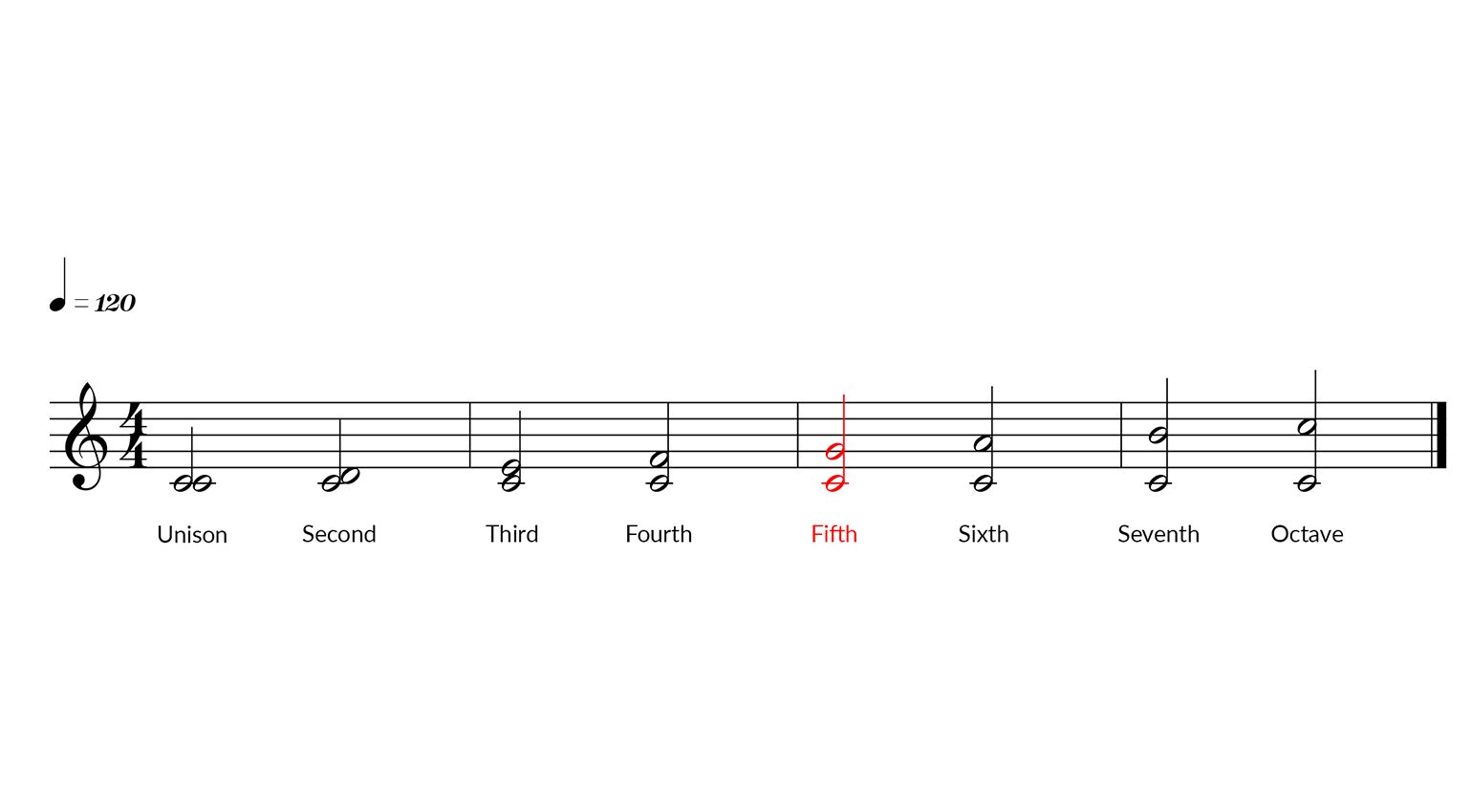

These are the first eight intervals. Their names derive from the positions they stand for. · Source: Tobias Homburger

Intervals in the Circle of Fifths

The interval fifth stands for the number “5”. This means: If you take the first and fifth notes of a major or minor scale, you get a fifth.

For an exact analysis, let’s now break down the fifth into half steps.

A perfect fifth consists of seven half steps (semitones). So if you count seven semitones starting from any note, you’ll always end up with a perfect fifth. And this interval is obviously very important for the Circle of Fifths – we’ll get into that later.

As the other part of the name explains, the keys are arranged in a circle. The starting point is always C major, which doesn’t have any accidentals. This key is located at the 12 o’clock position. On the right side of the circle are the sharp keys (♯), then on the left side are the flat keys (♭). The spot in the center at the bottom is particularly important: here, two keys meet, namely F-sharp and G-flat major. If you’re a pianist, you’ll be familiar with the phenomenon that each of the black keys can have different names. This phenomenon is called enharmonic equivalent.

What is an enharmonic equivalent?

In music, an enharmonic equivalent is the phenomenon where the same pitch is given a different name depending on the accidental [♭or ♯].

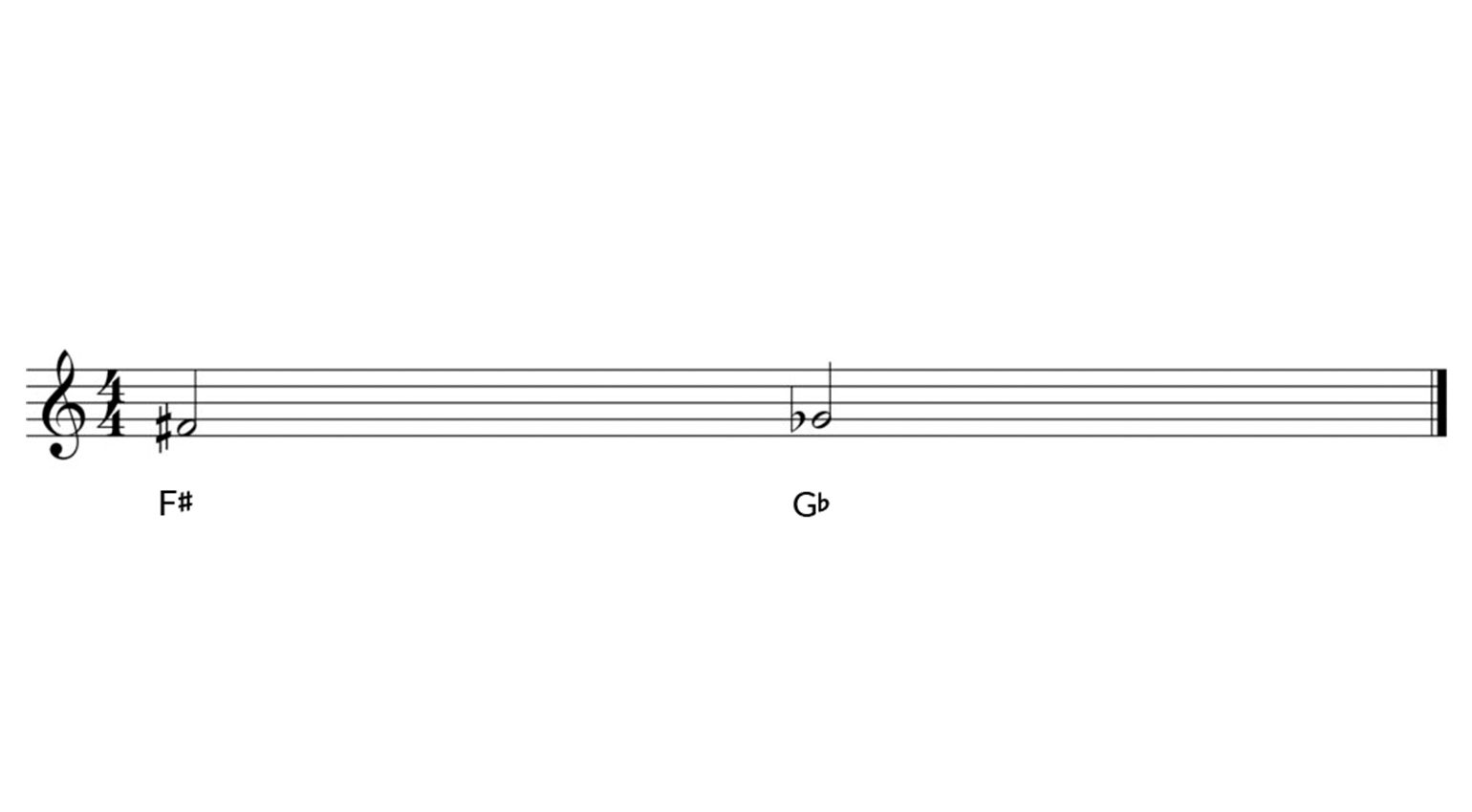

Example: ‘F‘ raised by a ♯ becomes ‘F♯‘, ‘G‘ lowered by a ♭ becomes ‘G♭’. F♯ and G♭ are the same pitch, but the name changes depending on which accidental is used. And while this distinction doesn’t matter for the sound, it’s actually very important for understanding the Circle of Fifths.

When two notes have different names but sound exactly the same, this is called enharmonic equivalent. · Source: Tobias Homburger

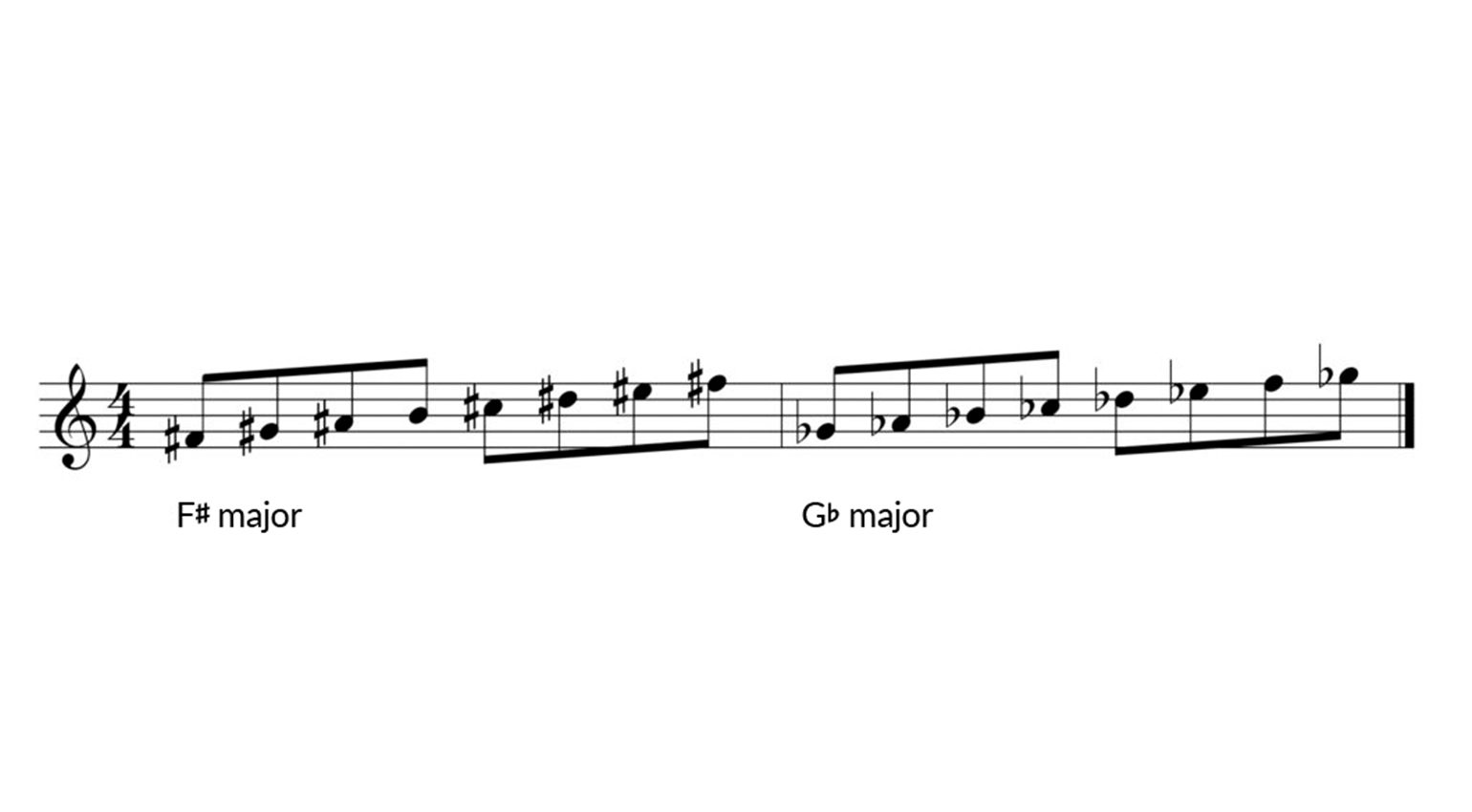

F♯ is the result of raising F by a half step; G♭ comes from lowering G by a half step. When you play both notes, you’ll hear the same pitch, but they’re called different names because the starting note is different in each case. This is what happens at the bottom of the Circle of Fifths. The keys of F-sharp and G-sharp major look completely different in notation (one has six sharps and the other has six flats), but both sound identical.

Here you can see the scales F sharp and G flat major. Although they look completely different, they sound exactly the same. · Source: Tobias Homburger

Minor Keys in the Circle of Fifths

Other keys appear inside the circle, but they are marked with small letters. These are the parallel minor keys that correspond to the major keys on the outside. Every major key has a parallel minor key. This means that there are always two keys with the same number of accidentals: A major key and a minor key. Using C major as an example, we can see that A minor is the parallel minor key. Both keys have no accidentals. They share the same notes but use different starting points. This is why parallel keys are related to each other. The parallel minor key is always three semitones below the major key.

How to use the Circle of Fifths

If you understand how the Circle of Fifths works, you can ‘calculate’ at any time which key you’re in. And that’s what I’m going to show you now.

The key without accidentals (neither ♯ nor ♭) is called C major. Counting seven half steps from here upwards, we arrive at G. If we play the C and the newly found G together, we hear a fifth, based on the root C (= key of C major = no accidentals). When we now use the G we just found as a starting point and count upwards another seven half steps, we arrive at D. Playing the G and the newly found D together, we again hear a fifth, based on the root G, which represents the next sharp key in the Circle of Fifths: Key of G major = one accidental (♯).

This exercise can now be continued in the same way. If you count to the right, you get the keys with the # sign. If you start from C and move seven half steps to the left, you reach the flat keys and land on F. The newly found key F also determines the key that has the first accidental in the range of the flat keys: Key of F major = one accidental (♭). Seven half steps (one fifth) to the left of the newly found note F, you reach the key of B♭ major, which is the second key in the range of the flat keys and therefore has two accidentals (♭). The fifth is, therefore, the defining unit of the Circle of Fifths, which makes it possible to determine the number of accidentals – always increasing by one.

How to find out the key of a piece

- Look at the type of accidentals and count them.

- Look for a “C” on the keyboard.

- For sharps (♯), move from the C to the right or up; for flats (♭), move to the left or down.

- However many accidentals you counted, that’s how many times you move a fifth away from the C.

- The note you arrive at shows you the key you’re possibly in. Possibly because there’s another key that has exactly the same accidentals: the parallel minor key. You’ll always find this three half steps below the major key.

- To determine whether you’re in a major key or in the parallel minor key, navigate to the last bar of your piece and look for the root note of the parallel minor. If you find it, your piece is likely written in this minor key. If you don’t find it, you’re likely in the parallel major key. In most pieces (but not all!), the final chord also reveals the actual key.

Major key or parallel minor key?

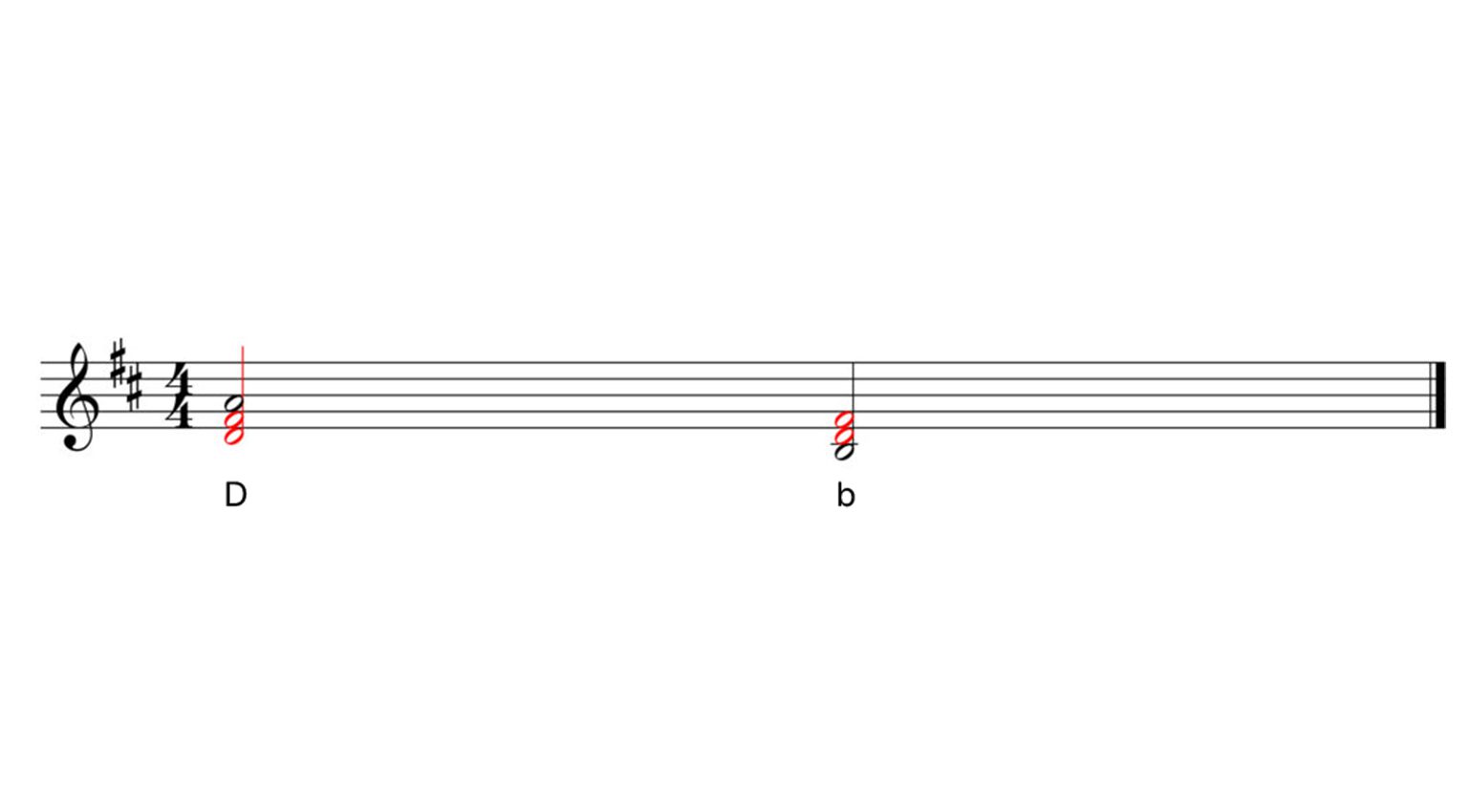

For example, the D major and B minor chords have two notes in common. If you search for the root note of the major key, i.e., the D, you’ll find it in both cases, but you won’t be able to make a final assessment. To find out if a piece is written in a major key or its parallel minor key, it’s best to look for the root note of the parallel minor in the last bar. Let’s look at an example.

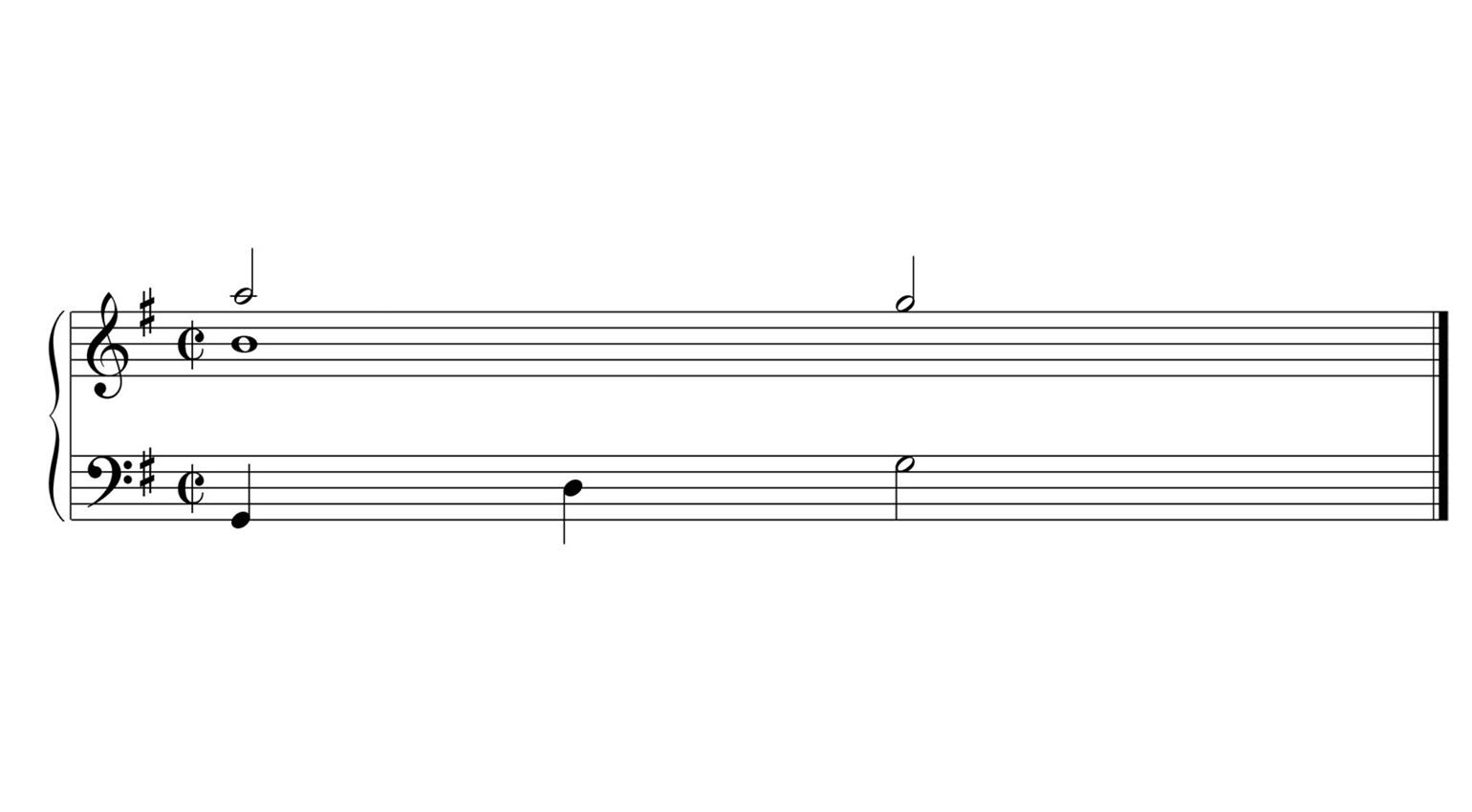

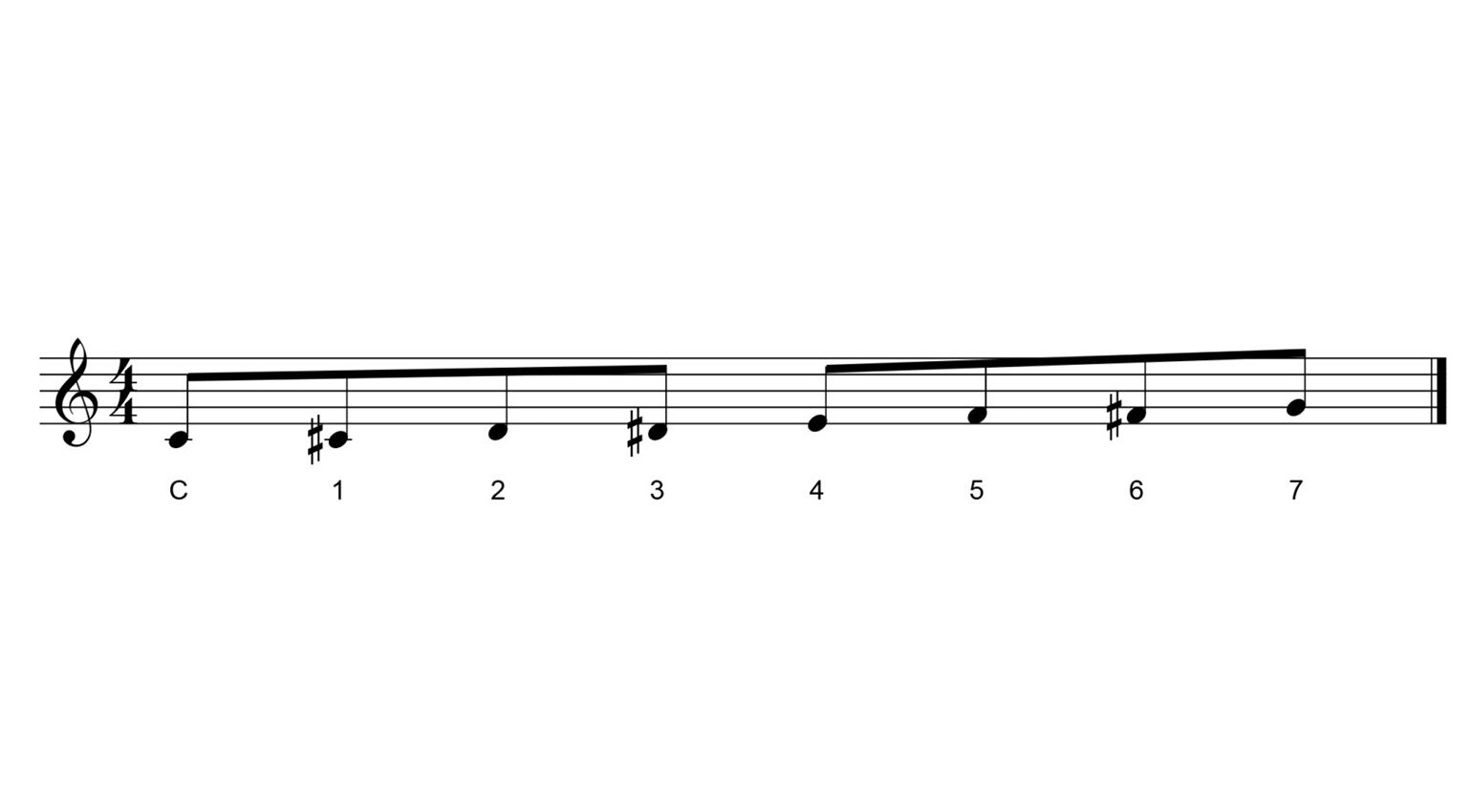

What do you see and what does that tell you?

- This piece is written in a key with one sharp (♯).

- Look for a C on the keyboard.

- Since this piece has a sharp (♯) as a key signature, you move to the right or up. So with only one sharp, you move up only one fifth, which is seven semitones.

- You end up with a G, so the piece could have been written in G major. Now determine the parallel minor key by counting down three semitones. You arrive on E, so the second possible key is E minor.

- Now look for the root note of the minor parallel in the last bar, i.e. an E.

- In this example, there’s no E in the last bar, so the piece is in G major.

In 99% of cases, you can find out in the last bar if the piece was written in major or minor. · Source: Tobias Homburger

If you stick to this plan, you can easily find out the key of any piece.

Finding scales and their notes

Building a scale based on accidentals

If you look closely, you’ll notice that there’s another thing in the Circle of Fifths that moves in fifths: the accidentals themselves. The first sharp (♯) is always F♯, the second C♯, the third G♯ and so on. With the flats (♭), it starts with B♭ and then continues with E♭, A♭, and so on.

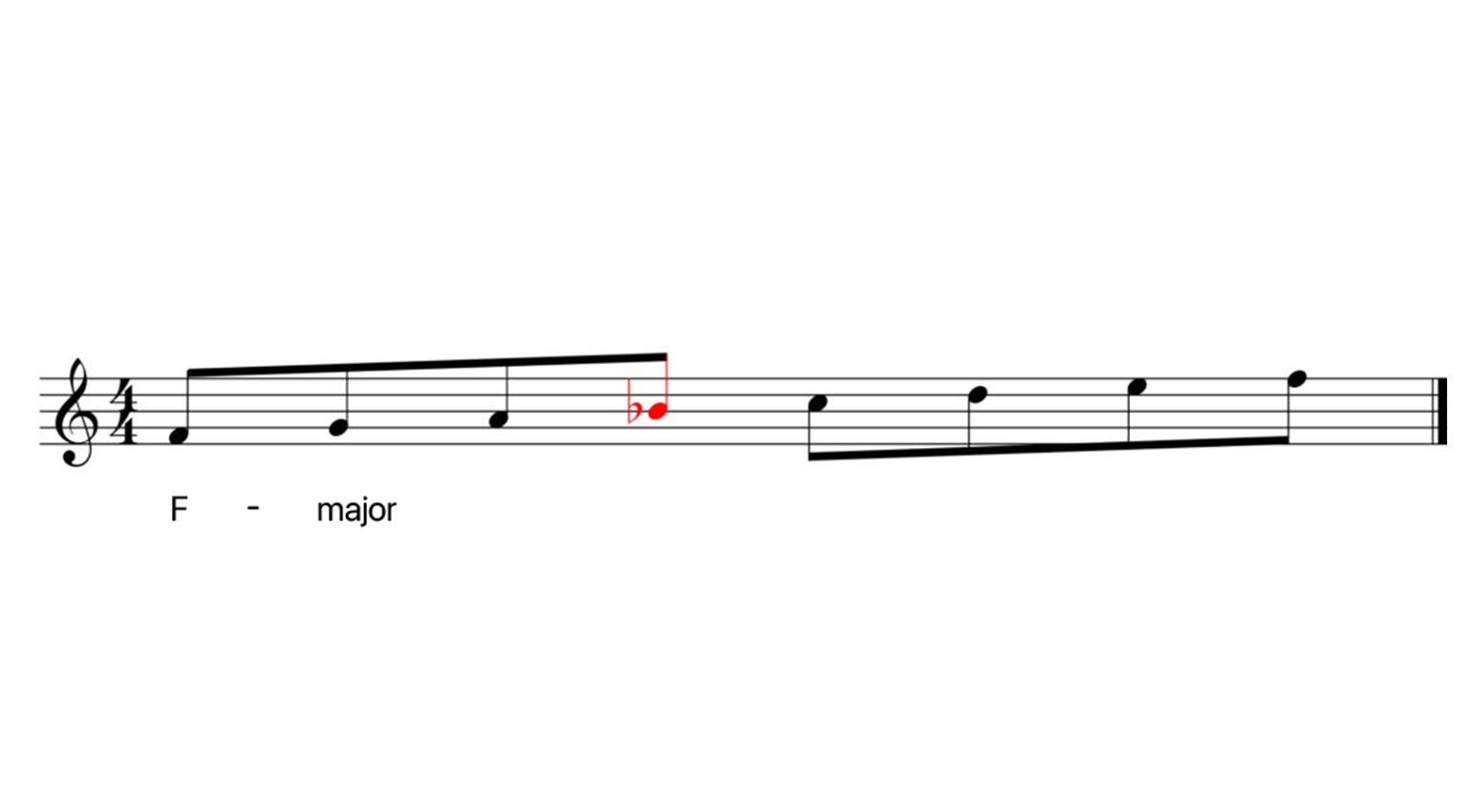

Let’s say you want to find out what an F major scale looks like. The first thing you do is determine the number of accidentals. The note F is exactly a fifth below C. This means, first of all: F major has only one accidental, namely one flat (♭). This turns the B into a B flat. On the piano, play from F upwards to the next F using only white keys, but replace the B with the B flat (B♭). And voilà – there’s your F major scale.

This process makes it easy to determine any major scale. If you play a scale with sharps, you have to raise the notes accordingly. Let’s take a look at this in detail.

Let’s say you want to know the notes of the D major scale. As always, begin at C (12 o’clock in the Circle of Fifths), go up a fifth (seven half steps) and end up on G. Now go up another fifth to arrive at D. You moved up twice, so that tells you that there are two sharps in D major. You also know that the first sharp is always F♯ and the second sharp is a fifth higher, which means C♯. All you have to do now is to play from D to the next D and substitute the F♯ and C♯ for the corresponding white keys.

Conclusion

The subject of the Circle of Fifths may seem a bit dry at first, but with a bit of practice, it really isn’t hard to understand. The Circle of Fifths is a simple method to determine the key of a piece of music and construct the corresponding scale. Once you’ve memorized the system, you’ll be able to identify keys in a snap.

More about Music Theory and the Circle of Fifths

Curious to find out more about music theory? Check out these excellent books*!

Further Reading

This article was originally published in German on bonedo.de.

* This post contains affiliate links and/or widgets. When you buy a product via our affiliate partner, we receive a small commission that helps support what we do. Don’t worry, you pay the same price. Thanks for your support!

2 responses to “The Circle of Fifths Demystified”

4,2 / 5,0 |

4,2 / 5,0 |

I like your lesson

Thank you for your article, this is very helpful in understanding the circle of fifths. I believe the proper term for the minor keys in the inside of the circle is “relative minor.” Parallel minor is when it shares the same starting note as the major but is the minor version. Ex. In C major, the relative minor is Am, and the parallel minor is Cm. The major and relative minor share the same key signature. The major and parallel minor share the same order of notes but the key signature is different.